February 2006: Sgt. Jon Trevino shot his estranged wife,

Carol Trevino, five times, the last time in the head. Then he shot himself. The

couple’s nine year old son sat in bed and watched his father kill his mother in

cold blood (Alvarez & Sontag, 2008).

September 2008: 19 year old Jacqwelyn Joann Villagomez was

beaten and choked to death by her boyfriend, John Wylie Needham. Needham was a

25 year old Iraqi veteran who suffered combat injuries. His family reported

that he returned home with severe mental problems, pain from the shrapnel in

his legs and back and struggled with nightmares that left him screaming

(Esquivel and Hanley, 2008).

August 2008: Jessie Bratcher, Iraqi war veteran and National

Guardsman, shot (10 times) and killed Jose Ceja Medina, the man he believed had

raped his girlfriend. It was later learned that Bratcher's Humvee was hit by a

roadside bomb in Iraq in 2005 but the team reported no injuries, though

Bratcher and his team leader both had headaches. It was not until 2008 that Bratcher’s

recurring anxiety, depression and mood swings were classified as a traumatic

brain injury from the blast -- symptoms which overlap and mimic post-traumatic

stress disorder (Sullivan, 2009).

April 2009: Less than a year after returning from combat in

Iraq, Nick Horner shot and killed Raymond Williams, a retired 64 year old in

Pennsylvania. Horner also killed a teenager and wounded a woman at a store in

the same town. Horner did not know any of these victims. After he returned from

Iraq, Horner was a different person, his mother said. He barely left his home

and, oftentimes, “his wife would find him crying in the corner of the basement”

(Lawrence & Rizzo, 2012).

How many more of these stories will it take before the

effects of war on our veterans are taken seriously?

(Lee, 2013)

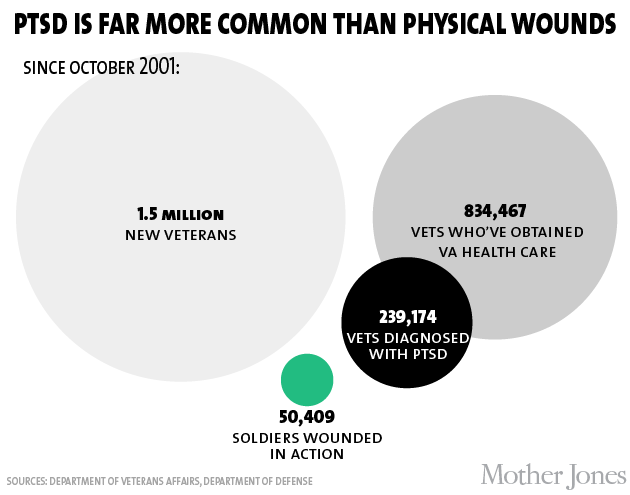

Nearly 20 percent of all Operation Enduring Freedom and

Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans screened positive for Post-Traumatic Stress

Disorder (PTSD) in 2008 (Banai, Maxwell, O’Neal, & Gallagher, 2011). The

actual rate of veterans with PTSD is probably much higher. The symptoms of

PTSD, according to the VA, are reliving the event, avoiding situations

reminiscent of the event, feeling numb, and hyperarousal. Hyperarousal is the

feeling jittery and always being on alert and on the lookout for danger (PTSD)

(National Center for PTSD, 2013). The effects of hyperarousal have been blamed

for the high rates of violence among veterans. Service members with PTSD (who

sought therapy) found that 80 percent committed a violent act within the past

year. This is six times higher than the civilian population (Banai et al., 2011).

Iraq and Afghanistan veterans who struggle with anger are twice as likely as

other vets to be arrested for crimes, according to the Journal of Consulting

and Clinical Psychology, which published a study last year (Fantz, 2013). In 2009, at least 122 soldiers who served in

Iraq and Afghanistan had been charged in or convicted of a killing. A 2009 Army

study of 11 killings committed by members of Fort Carson, Colorado concluded

that those soldiers were affected “by combat in Iraq, alcohol and drug abuse,

previous mental health issues and PTSD” (Sullivan, 2009).

(Lee, 2013)

The mental instability, anxiety and anger associated with

PTSD are destructive for most military families. PTSD increases the chance of

family violence, divorce and drug and alcohol abuse. A veteran suffering from PTSD may be unable to

fulfill his or her roles as a parent, spouse or contributing member of society.

This puts a considerable amount of strain on the family. Despite the fatal

effects of PTSD, most military families do not seek treatment for PTSD because

of the stigma associated with mental disorders (Banai et al., 2011). Unfortunately, treatment for this condition

is not readily available for those veterans willing to reach out for help.

Take the story of Jessie Bratcher (the Vet who killed the

alleged rapist of his girlfriend): After returning home from war, his grandfather heard him at night, "hollering, a bunch

of mumbo jumbo, like a frightened child” and Jessie continuously asked for guns

(Sullivan, 2009). Bratcher

went to the VA for help because he was unable to work but his attempt to

collect benefits was denied. The VA decided that his PTSD symptoms were

"too mild." Though

it's widely treated, the number of Iraq and Afghanistan vets compensated for PTSD

is fewer than 2 percent of veterans receiving benefits. “Nationally, almost 4

percent of World War II and Korean vets and 7 percent of Vietnam vets receive

money for PTSD” (Sullivan, 2009). Not

only is compensation for symptoms of PTSD difficult for vets to receive, but

proper counseling is also scarce. There are not a high number of therapists who

are experts in PTSD and who understand how to really help the victims. Vets may

not want to talk to a civilian who has no idea about the terror he/ she has

gone through. More research needs to be put into different strategies to help

these vets.

(Lee, 2013)

Sergeant Trevino had been treated twice for mental health

problems before the war: once for serious depression as his first marriage

crumbled, and then again for post-traumatic stress disorder stemming from the

childhood sexual abuse and also marital problems with his new wife, Carol. He

was counseled and treated with medication both times. The Air Force was fully

aware of the instability of Trevino’s mental state yet military doctors

certified that he could handle the job. The Air Force considers the stress

disorder to be treatable and is willing to deploy an airman with a history of

it. When Trevino returned home from his deployment, Trevino began taking a mix of

antidepressants and therapy prescribed by the military. However, the damage had

already been done (Alvarez & Sontag, 2008). The Air Force, the institution

that Trevino had dedicated his life and loyalty to, had greatly betrayed him

and his family by failing to safeguard the health of their soldier before

anything else. Unfortunately, this is not a common occurrence since the need

for soldiers overseas is greater than our actual numbers.

(Lee, 2013)

The reality of PTSD within our military population is

overwhelming. Not only does PTSD

increase the likelihood of violence for families and society, it also increases

the incidence of self-inflicted violence. These images give us a clear picture

of the effect of PTSD on the well-being of our nation’s heroes.

(Lee, 2013)

I hope that within the next few years we will see an

increase in PTSD specialists and funding for rehabilitation programs. Although

not all returning vets have PTSD, a significant amount does and they need our

attention and support.

Questions:

1.

Why would military families not want to seek out

treatment for PTSD?

2.

Should universities offer concentrations or

specializations in PTSD therapy?

*If you enjoy watching those surprise coming home videos,

here is the video of when one of my best friends surprised us on Christmas last

year. Enjoy!*

Leandra Furtado

References:

Alvarez, L. &

Sontag, D. (February 2008). When Strains on Military Families Turn Deadly. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/02/15/us/15vets.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Banai, M.,

Maxwell, B., O’Neal, J., Gallagher, M. (2011, December ). Unsung Heroes:

Military Families after 10 Years of War. In IAVA

Issue Report: December 2011. Retrieved from https://my.lesley.edu/courses/1/13-SP.CSOCL.2402.01.73885/content/_1124354_1/Unsung_Heroes.pdf

Esquivel

P. & and Hanley, C. (September 2008). 'Mentally unstable' Iraq veteran

arrested in death of girlfriend, 19. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-me-beating3-2008sep03,0,6026971.story

Fantz,

A. (February 1013). Sniper Killing Aftermath: 5 Things to Know about PTSD. CNN Health. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2013/02/05/health/ptsd-five-things

Lawrence,

C. & Rizzo, J. (May 2012). Under Fire: Wartime Stress as a Defense for

Murder. CNN Justice. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2012/05/05/justice/ptsd-murder-defense

Lee, J.(January 2013). Charts: Suicide, PTSD and the Psychological Toll on America's Vets. Mother Jones. Retrieved from http://www.motherjones.com/politics/2013/01/charts-us-veterans-ptsd-war-iraq-afghanistan

Sullivan,

J. (October 2009). Trauma in Iraq leads to drama in Oregon. The Oreganian.

Retrieved from http://www.oregonlive.com/news/index.ssf/2009/10/post_25.html.

National

Center for PTSD. (2013). What is PTSD? United

States Department of Veteran Affairs. Retrieved from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/what-is-ptsd.asp

Leandra Furtado

No comments:

Post a Comment